Tumor growth and angiogenesis is impaired in CIB1 knockout mice

Journal of Angiogenesis Research. 2010;

Received: 17 April 2010 | Accepted: 30 August 2010 | Published: 30 August 2010

Vascular Cell ISSN: 2045-824X

Abstract

Background

Pathological angiogenesis contributes to various ocular, malignant, and inflammatory disorders, emphasizing the need to understand this process more precisely on a molecular level. Previously we found that CIB1, a 22 kDa regulatory protein, plays a critical role in endothelial cell function, angiogenic growth factor-mediated cellular functions, PAK1 activation, MMP-2 expression, and

Methods

To test this hypothesis, we allografted either murine B16 melanoma or Lewis lung carcinoma cells into WT and CIB1-KO mice, and monitored tumor growth, morphology, histology, and intra-tumoral microvessel density.

Results

Allografted melanoma tumors that developed in CIB1-KO mice were smaller in volume, had a distinct necrotic appearance, and had significantly less intra-tumoral microvessel density. Similarly, allografted Lewis lung carcinoma tumors in CIB1-KO mice were smaller in volume and mass, and appeared to have decreased perfusion. Intra-tumoral hemorrhage, necrosis, and perivascular fibrosis were also increased in tumors that developed in CIB1-KO mice.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that, in addition to its other functions, CIB1 plays a critical role in facilitating tumor growth and tumor-induced angiogenesis.

Background

Pathological angiogenesis is a hallmark of tumorigenesis and is a discrete event in solid tumor formation [1, 2]. Unlike physiological forms of angiogenesis that occur during embryonic development and normal wound healing, pathological, tumor-induced angiogenesis often ensues due to imbalances in either angiogenic activators or inhibitors [1, 3]. Recent pre-clinical and clinical studies have employed strategies to target tumor vasculature as a means to impede tumor growth and eventual metastasis [4, 5]. However, thus far monotherapy with such agents in human subjects has been limited due to marginal effectiveness, toxicities, and relative lack of specificity [6, 7]. Therefore, further exploration is currently underway for more specific drug targets that are not essential for physiological forms of angiogenesis.

CIB1 is a 22 kDa EF-hand-containing regulatory protein that was originally identified as a binding partner for the cytoplasmic tail of the platelet integrin αIIb, and later found to inhibit αIIbβ3 activation in megakaryocytes [8, 9]. Subsequently however, CIB1 was found to be widely expressed in various organs, tissues, and cell types, which suggested that it likely has additional uncharacterized roles [10, 11]. Accordingly, we and others have demonstrated that CIB1 binds to and regulates the activity of various proteins including the transcription factor PAX3 [12], the polo-like kinase Fnk and Snk [13], the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor [14], Rac3 [15], PAK1 [16], and FAK [17]. Among these binding partners, PAK1 and FAK are known to regulate endothelial cell (EC) function

Recently, we reported that CIB1 is not required for developmental angiogenesis, as CIB1-KO mice are viable and female mice are fertile [9]. However, CIB1 is essential for proper EC signaling and functions such as migration, proliferation, and nascent tubule formation [21]. Loss of CIB1 in ECs also leads to attenuated responses to angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF and FGF-2, which result in decreased expression of the zinc-requiring matrix-degrading proteinase MMP-2. Moreover, CIB1-KO mice are impaired in pathological as well as adaptive forms of ischemia-induced angiogenesis, and PAK1 and ERK1/2 activation are significantly decreased in CIB1-KO ECs and ischemic muscle tissue [21]. Although these data clearly demonstrate that CIB1 participates in ischemia-induced angiogenesis

As in ischemia-induced angiogenesis, tumor-induced angiogenesis is highly dependent on angiogenic growth factors and MMPs [22–24]. Accordingly, tumor allografts in knockout mice for growth factors such as FGF-2 and MMPs such as MMP-2 and MMP-9 exhibit significantly reduced tumor growth and tumor-induced angiogenesis [1, 25, 26]. Since our previous studies demonstrated that CIB1-KO mice have decreased growth factor-mediated angiogenesis, and CIB1-KO ECs have attenuated MMP-2 expression, we hypothesized that CIB1-KO mice may also have a defect in tumor-induced angiogenesis. To test this conjecture we allografted CIB1-KO mice with murine tumor cells that endogenously expressed either very low levels (B16 melanoma tumor cells) or very high levels (Lewis lung carcinoma cells) of MMP-2, as previously demonstrated by zymography analysis [25]. We report here that, in addition to regulating tumor growth, CIB1 in the host significantly contributes to tumor-induced angiogenesis.

Methods

Allografts

Male WT and CIB1-KO mice between 15 and 18 weeks old were anesthetized with 1.125% isoflurane supplemented with 2:3 oxygen-air. Rectal temperature was closely maintained at 37.0 ± 0.5°C. Hair was removed from the hind-limb ventral adductor thigh region using depilating cream, with care to avoid erythema. Mice were given a single subcutaneous injection of either 5 × 105 B16 melanoma cells (purchased from UNC-CH Tissue Culture Facility) or 2.5 × 105 Lewis lung carcinoma cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) that were impregnated in 50 μL of 50% growth factor reduced Matrigel. Tumor allografts were grossly inspected 14 days after tumor cell injections, and photographs were obtained to document differences in tumor morphology between WT and CIB1-KO mice (

Tumor fixation, histology, and capillary density assessment

Tumors isolated from animals were fixed in 2% PFA for 48 h, with a solution change at 24 h. Tumors were rinsed in water, placed in 70% ethanol for 48 h with shaking and another change of solution at 24 h. Four biopsies (~2-3 mm in size) were obtained from both the center and periphery of each tumor and embedded in paraffin. At least 3 interrupted sections, 6 μm thick and 50 μm apart, were obtained and stained with either H&E, or Masson's trichrome (MT), a marker for fibrosis-associated collagen deposition[27]. For each tumor, one random interrupted section of all four biopsies was assessed for the incidence of necrosis or intra-tumoral bleeding, spanning 70% of the biopsy tissue section. Similarly, one random interrupted section of each biopsy was assessed for the incidence of perivascular fibrosis.

To assess capillary density, the plasma membranes of capillary ECs in tumor sections were labeled with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated isolectin GSL-1-B4 (1:100; Invitrogen), or with primary rat anti-mouse CD31 (PECAM-1) antibody (1:50; Pharmingen) and subsequently Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary goat anti-rat IgG (1:1000; Invitrogen). Using a Nikon TE2000U inverted fluorescent microscope with an OrcaER, four high magnification immunoflorescent and H&E images were collected for each biopsy to yield a total of 16 images per tumor specimen. Using ImageJ software, the number of vessels with a clear lumen and < 7 μm were counted by an independent observer, who was blinded as to animal genotypes. Tumor microvessel density was reported as the average number of microvessels per high-magnification frame.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were compared with the Student's

Results and Discussion

Almost all tumor cells secret angiogenic growth factors and MMPs (such as MMP-2 and MMP-9) to recruit and stimulate new blood vessel formation [1, 28]. Since we reported previously that CIB1-KO mouse tissue and ECs have reduced growth factor-induced angiogenesis and MMP-2 expression [21], we asked whether CIB1-KO mice also have a defect in tumor-induced angiogenesis. To address this question we subcutaneously injected the adductor hindlimb regions of WT and CIB1-KO mice with B16 melanoma tumor cells (which are known to secrete angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF, FGF-2, PDGF, but only very low levels of gelatinases MMP-2 and MMP-9), and Lewis lung carcinoma tumor cells (which, in addition to secreting various angiogenic growth factors, secrete higher levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9) [29].

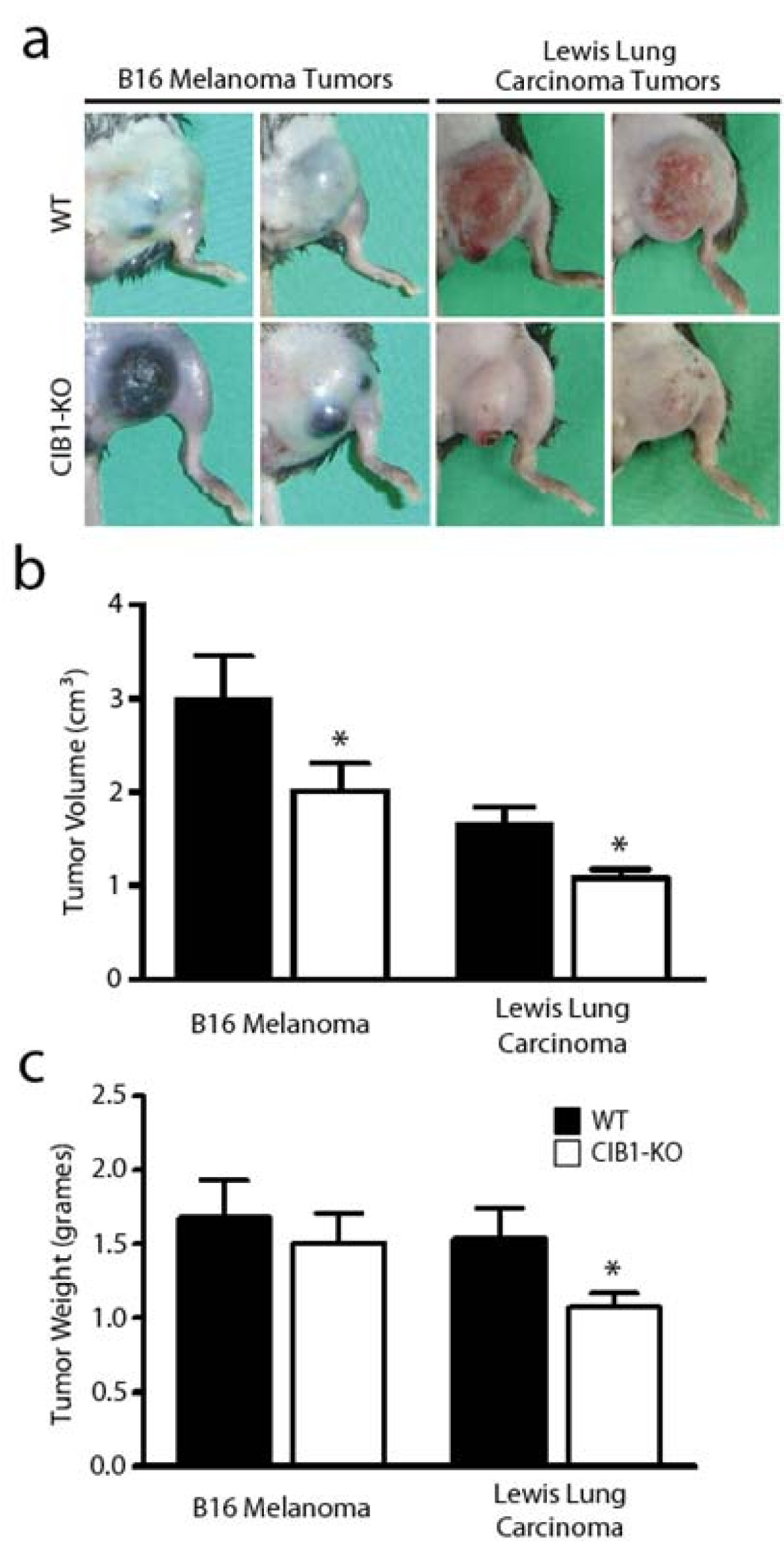

Fourteen days after tumor cell injection, signs of melanoma tumor necrosis were evident in a large subset of CIB1-KO mice (Figure 1a). Tumors in approximately 64% of CIB1-KO mice demonstrated evidence of gross morphological necrosis compared to 33% of WT mice (Table 1). This observation prompted us to immediately terminate the study and harvest allografted tumors from WT and CIB1-KO mice for further analysis. Gross dissection of melanoma tumors from CIB1-KO mice revealed that a large subset of these tumors were composed of highly necrotic fluid-laden tissue, and surrounded by small pockets of bleeding. In contrast, melanoma tumors extracted from WT mice were more homogenous and dense, and surrounded by less areas of bleeding. Furthermore, melanomas extracted from CIB1-KO mice were significantly reduced in volume (32% decrease,

Figure 1

Figure 1 caption

Allograft tumors in CIB1-KO mice are smaller and have a distinct morphological appearance. (a) Two representative images of B16 melanoma tumors or Lewis lung carcinoma tumors that developed after 14 days in either WT or CIB1-KO mice. Tumors in CIB1-KO mice had a distinct morphological appearance, with gross necrosis of melanoma tumors and blanching of carcinoma tumors. (b, c) Tumors that developed in CIB1-KO mice were smaller in volume and weight compared to WT mice, but no significant difference was noted for melanoma tumor weight. Error bars are ± SEM (n = 8-11 mice per group; * < 0.05).

Interestingly, unlike the allografted melanoma tumors, none of the Lewis lung carcinoma tumors that developed in CIB1-KO and WT mice demonstrated evidence of gross morphological necrosis (Table 1 and Figure 1a). Compared to melanoma tumors, the complete lack of gross necrosis in carcinoma tumor in CIB1-KO mice may be due to differences in the physiology and cellular metabolic demand of Lewis lung carcinoma cells. Alternatively, this difference may be attributed to the ability of Lewis lung carcinoma cells to express and secrete high levels of MMP-2, which does not occur as effectively in B16 melanoma cells. Nevertheless, similar to melanoma tumors in CIB1-KO mice, Lewis lung carcinomas were also 30% reduced in weight and 35% reduced in volume when compared to these carcinomas in WT mice (

Moreover, carcinomas in CIB1-KO mice also appeared more blanched (Figure 1a), which suggested that these tumors were not as well perfused. To measure perfusion in Lewis Lung carcinoma tumors we used a non-invasive Doppler flowmeter for periodic assessment of tumor perfusion in real-time. Doppler perfusion of melanoma tumors in CIB1-KO mice was not assessed since they appeared to be grossly necrotic in appearance. Doppler images of 14 day old carcinomas demonstrated areas of clearly higher tumor perfusion in WT, but not CIB1-KO mice (areas in white; Additional file 1: Figure 1a). Quantification of these data also demonstrated a trend of reduced carcinoma tumor perfusion in CIB1-KO mice. However, due to variations in tumor dimensions and orientation, no overall statistically significant differences were extrapolated from this analysis (Additional file 1: Figure 1b). Nevertheless, like melanoma allografts, the decreased size and differences in carcinoma allograft gross appearance in CIB1-KO mice suggest that these tumors were not growing as efficiently as carcinomas in WT mice.

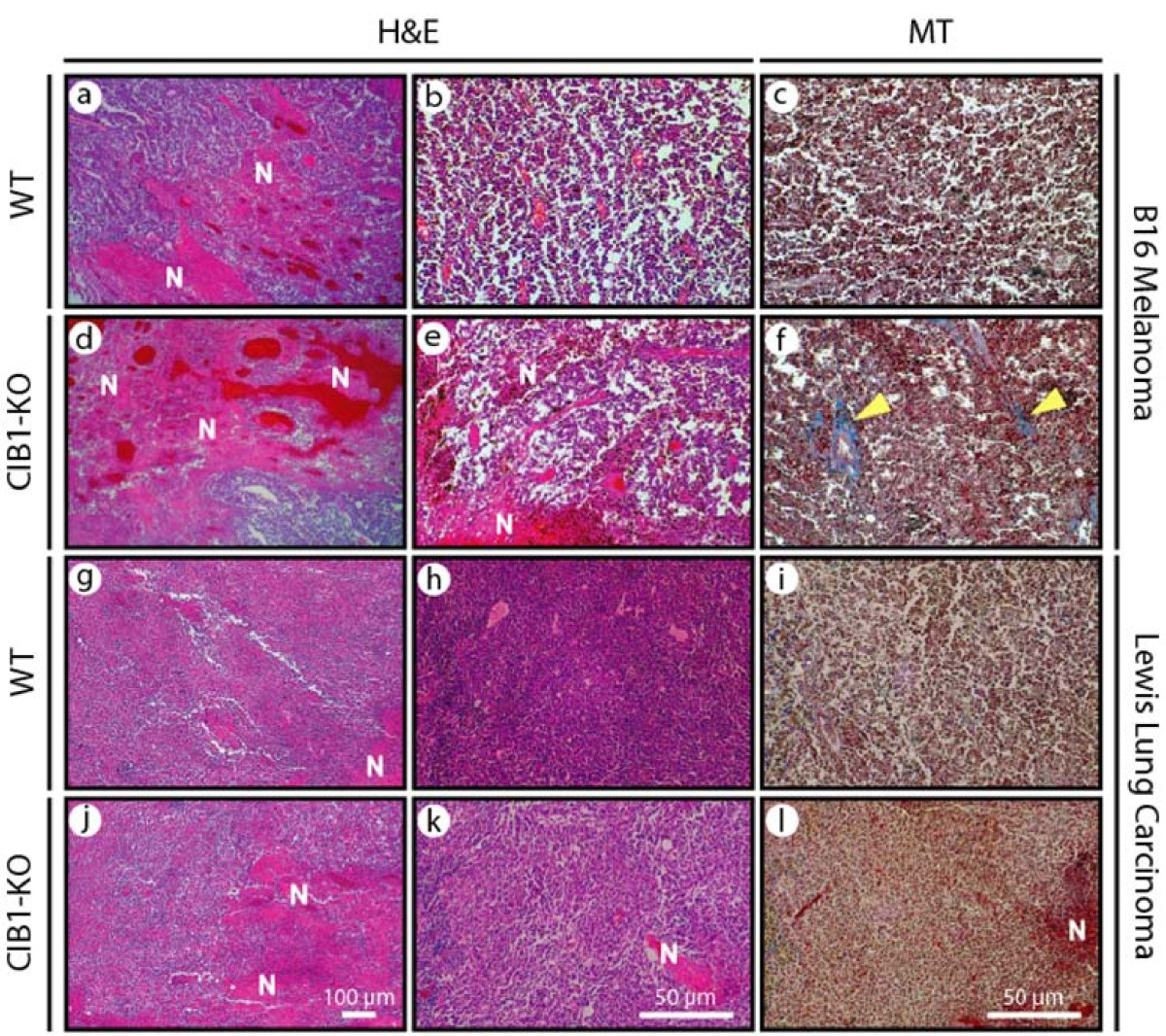

To further assess the allograft melanoma and carcinoma micro-environments we obtained biopsies from allograft tumor peripheries and centers. To minimize sample bias, biopsies were obtained from random locations and we histologically examined random areas of each biopsy section. Histological examination at low and high magnification of melanoma biopsies from WT and CIB1-KO mice revealed areas of tumor necrosis and intra-tumoral bleeding. However, melanoma biopsies from CIB1-KO mice contained larger areas of tumor necrosis and intra-tumoral bleeding (Figure 2a, b, d, and 2e). Similarly, intra-tumoral and perivascular fibrosis, associated with tissue injury and fibrosis, was more frequently found in melanoma tumors in CIB1-KO mice (Figure 2c and 2f). Although these differences in perivascular fibrosis, and intra-tumoral necrosis and bleeding (that span at least 70% of a biopsy's surface area) were not statistically significant in melanoma tumors, the incidences were higher in CIB1-KO mice compared to WT mice (

Figure 2

Figure 2 caption

Increased microscopic necrosis and bleeding in CIB1-KO allograft tumors. Fourteen days after tumor cell injection, tumors were isolated from animals and fixed. Sections were sectioned and stained with H&E or Masson's trichrome (MT) as described in Methods. Representative images were captured at two different magnifications using a Nikon D100 camera attached to a Nikon inverted microscope. Representative low magnification images (a, d, g, and j), and high magnification (b, c, e, f, h, i, k, and l) of melanoma and carcinoma tumors. Areas of necrosis (N) and bleeding are noted on H&E-stained sections (a, b, d, e, g, h, j, and k). Fibrosis stained in blue (identified with yellow arrows) is noted on MT-stained sections (c, f, i, and l).

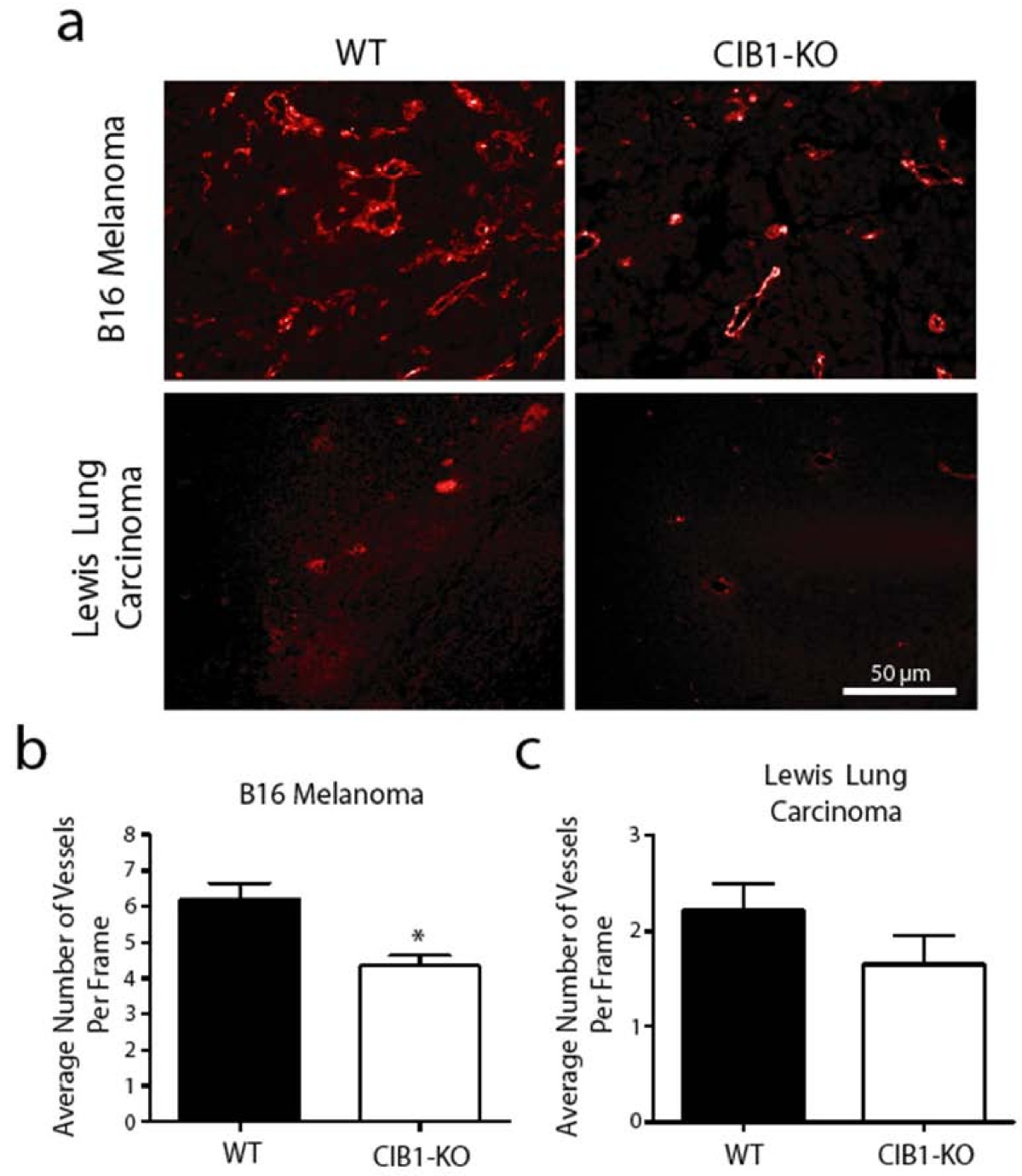

Reduced tumor size and increased tumor necrosis observed in CIB1-KO allografts may also be due to reduced tumor-induced angiogenesis that is necessary for efficient delivery of oxygen and essential nutrients to the proliferating tumor cells. Thus, we assessed the microvessel density in sections obtained from biopsies of melanoma and carcinoma allografts that developed in both CIB1-KO and WT mice with either PECAM-1 or Isolectin GSL1-B4. Isolectin GSL1-B4-stained microvessels were noted in melanoma tumor sections, and similarly PECAM-1-stained microvessels were noted in carcinoma tumor sections (Figure 3a). The PECAM-1 antibody did not stain microvessels in melanoma tumors, and isolectin GSL1-B4 stained Lewis lung carcinoma cells (data not shown). At high magnification we observed that the microvessel density in melanoma tumors in CIB1-KO mice was 29% less than that observed in tumors isolated from WT mice (

Figure 3

Figure 3 caption

Melanoma in CIB1-KO mice have reduced vascularization. (a) Representative immunoflorescent images of Isolectin GSL1-B4-stained melanoma tumor sections and PECAM-1-stained carcinoma tumor sections. The number of vessels with a clear lumen and < 7 μm in melanoma (b) and carcinoma (c) tumors were counted by a blinded observer. Tumor microvessel density is reported as the average number of intra-tumoral microvessels per frame. Error bars are ± SEM ( = 7 - 11 mice per group; * < 0.05).

The decreased microvessel density in allografted tumors in CIB1-KO mice may be due to decreased expression and secretion of MMP-2 by CIB1-KO ECs, which we reported previously [21]. Itoh

The combination of increased tumor necrosis and decreased tumor-induced angiogenesis in CIB1-KO mice may also be a direct result of attenuated EC signaling in these mice. As previously reported, ECs deficient in CIB1 have reduced PAK1 activation. The activation of this serine/threonine kinase is an important point of convergence between growth factor- and integrin-induced signaling that is mediated by small GTP-bound GTPases such as Cdc42 [30, 31]. Leisner et al. demonstrated that CIB1 binds to PAK1, thus preventing its interaction with Cdc42 and subsequent activation in various cell types [16]. Since PAK1 primarily mediates its effects on ECs via the Ras-Raf-ERK1/2 MAPK signaling pathway [18], we previously tested whether MAPK signaling is affected when CIB1 is not present. ERK1/2, but not p38, MAPK signaling was significantly attenuated in CIB1-KO ECs

There may also be alternative mechanisms by which CIB1 mediates its effects on tumor growth and neovascularization. We have observed decreased monolayer resistance in CIB1-KO ECs (unpublished data), suggesting that CIB1 is necessary for proper EC monolayer permeability

Conclusions

Taken together, our findings support a model in which CIB1 plays an important role in regulating tumor viability, growth, and angiogenesis. We propose that CIB1 mediates these effects at least in part through its previously characterized role in PAK1-ERK1/2-MMP-2 signaling. The fact that more necrosis and bleeding was noted in melanoma tumors in CIB1-KO mice, where there is a relative lack of MMP-2, suggests that this mechanism may be a major pathway mediating the observed effects in this study. Hence the data herein establish a regulatory role for CIB1 in tumor growth and pathological tumor-induced angiogenesis.

Authors' information

MAZ carried out these studies in partial fulfillment for the PhD degree while enrolled in the MD/PhD program at UNC-CH. MAZ is currently a vascular surgery resident at Stanford University Medical Center.

WY created the CIB1 knockout mice and is an expert molecular biologist.

DC is a postdoctoral research associate in the Department of Cell and Molecular Physiology at UNC-CH.

JEF is a full professor in the Department of Cell and Molecular Physiology at UNC-CH. He is expert in physiologic and genetic regulation of collaterogeneis and angiogenesis during development and disease, as well as in vascular wall growth and remodeling.

LVP was the thesis advisor for MAZ. She is also full professor and Chair of the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics at UNC-CH. Her lab originally discovered CIB1 and she is an expert on integrin mediated adhesion and signal transduction in vascular cells.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Carcinoma tumors in CIB1-KO mice have less areas of high perfusion. Carcinoma tumors in CIB1-KO mice have reduced perfusion. Superficial hind-limb ventral adductor thigh regions, where tumor cells were injected, were monitored with noninvasive scanning laser-Doppler perfusion imaging (model LD12-IR, Moor Instruments; modified for high resolution and depth of penetration (2 mm) with an 830 nm-wavelenght infrared 2.5 mW laser diode, 100 μm beam diameter, and 15 kHz bandwidth). Isofluorane anesthesia and rectal temperature (37 ± 0.5°C) were maintained the same for all measurement days and among animals. (a) Laser-Doppler perfusion imaging at the site of tumor injection pre- (day 1), and day-7 and -14 after tumor cell injection. Image scans are assembled from the mean Doppler velocity (in perfusion units, PU) for each 100 × 2000 μm voxel in the scan area. (b) Regions of interest (ROI) were drawn around tumor perimeters, to derive a tumor area, and determine what percentage of the area had a detectable Doppler signal. For every given ROI, a tumor perfusion index was calculated using: (Average PU) × (ROI area) × (% ROI with detectable Doppler signal)/10,000. Error bars are ± SEM (n = 8-9 mice per group). (PNG 347 KB)

Acknowledgements

We thank Kirt McNaughton for assistance with tissue sectioning and staining, the UNC-CH Michael Hooker Microscopy Facility for imaging assistance, and Dr. William Barry for preliminary microarray data analysis. We also thank Dr. Howard Fried for editorial suggestions. This work was supported by grants from NIH 2-P01-HL45100 and 1RO1HL092544 (L. V. Parise), NIH HL-62584 (J. E. Faber), NIH T32-HL-069768 and NIH T32-GM008719 (M. A. Zayed).

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Authors’ original file for figure 2

Authors’ original file for figure 3

References

- Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249-257.

- Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell. 1996;86:353-364.

- Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature. 2005;438:932-936.

- Angiostatin induces and sustains dormancy of human primary tumors in mice. Nat Med. 1996;2:689-692.

- Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335-2342.

- Managing patients treated with bevacizumab combination therapy. Oncology. 2005;69(Suppl 3):25-33.

- Anti-angiogenic drugs: from bench to clinical trials. Med Res Rev. 2006;26:483-530.

- Identification of a novel calcium-binding protein that interacts with the integrin alphaIIb cytoplasmic domain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4651-4654.

- CIB1 is an endogenous inhibitor of agonist-induced integrin alphaIIbbeta3 activation. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:169-175.

- Structure, expression profile, and chromosomal location of a mouse gene homologous to human DNA-PKcs interacting protein (KIP) gene. Mamm Genome. 1999;10:315-317.

- Calcium-dependent properties of CIB binding to the integrin alphaIIb cytoplasmic domain and translocation to the platelet cytoskeleton. Biochem J. 1999;342(Pt 3):729-735.

- The EF-hand calcium-binding protein calmyrin inhibits the transcriptional and DNA-binding activity of Pax3. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1574:321-328.

- The polo-like protein kinases Fnk and Snk associate with a Ca(2+)- and integrin-binding protein and are regulated dynamically with synaptic plasticity. EMBO J. 1999;18:5528-5539.

- CIB1, a ubiquitously expressed Ca2+-binding protein ligand of the InsP3 receptor Ca2+ release channel. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20825-20833.

- The small GTPase Rac3 interacts with the integrin-binding protein CIB and promotes integrin alpha(IIb)beta(3)-mediated adhesion and spreading. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8321-8328.

- Essential role of CIB1 in regulating PAK1 activation and cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:465-476.

- Calcium-and integrin-binding protein regulates focal adhesion kinase activity during platelet spreading on immobilized fibrinogen. Blood. 2003;102:3629-3636.

- Differential alphav integrin-mediated Ras-ERK signaling during two pathways of angiogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:933-943.

- A dominant-negative p65 PAK peptide inhibits angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2002;90:697-702.

- Conditional knockout of focal adhesion kinase in endothelial cells reveals its role in angiogenesis and vascular development in late embryogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:941-952.

- CIB1 regulates endothelial cells and ischemia-induced pathological and adaptive angiogenesis. Circulation Research. 2007;101:1185-1193.

- Molecular regulation of vessel maturation. Nat Med. 2003;9:685-693.

- Matrix metalloproteinases in development and disease. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2006;78:1-10.

- Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature. 2000;407:242-248.

- Reduced angiogenesis and tumor progression in gelatinase A-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1048-1051.

- Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:737-744.

- Blood flow influences vascular growth during tumour angiogenesis. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:780-786.

- Gelatinase-mediated migration and invasion of cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1755:37-69.

- Induction of 103-kDa gelatinase/type IV collagenase by acidic culture conditions in mouse metastatic melanoma cell lines. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:11424-11430.

- Role of group A p21-activated kinases in activation of extracellular-regulated kinase by growth factors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36609-36615.

- A brain serine/threonine protein kinase activated by Cdc42 and Rac1. Nature. 1994;367:40-46.

- Involvement of endothelial PECAM-1/CD31 in angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:671-677.

- Genetic evidence for functional redundancy of Platelet/Endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1): CD31-deficient mice reveal PECAM -1- dependent and PECAM-1-independent functions. J Immunol. 1999;162:3022-3030.

- Antibody against murine PECAM-1 inhibits tumor angiogenesis in mice. Angiogenesis. 1999;3:181-188.