Hemangioblastoma: an updated primer

Vascular Cell. 2025;

Received: 26 August 2025 | Accepted: 23 September 2025 | Published: 03 October 2025

Vascular Cell ISSN: 2045-824X

Abstract

Hemangioblastomas are benign, WHO grade 1 tumors of vascular origin that occur in one or more regions of the central nervous system (CNS), but can also develop in other regions of the body [1]. They are capillary-rich neoplasms of the CNS that contain variably lipidized neoplastic stromal cells of unknown histogenesis [2]. Common areas of occurrence in the CNS include the cerebellum, spinal cord, and retina. Other areas where they can occur outside the CNS include organ systems such as the kidneys, liver, and pancreas. Since hemangioblastomas are usually benign and often curable if removed, they are classified as WHO grade I tumors when they occur in the CNS. Hemangioblastomas arise either in the setting of von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) disease or, more commonly, as a solitary sporadic lesion without additional stigmata or a family history [3]. VHL disease is an autosomal dominant inherited disorder caused by a germ-line mutation of the VHL gene located on the short arm of chromosome 3 (3p25-26) [2]. The presence of this mutated gene is characterized by intracranial or intraspinal hemangioblastomas, retinal angiomas, cystic lesions of the pancreas and epididymis, benign and malignant renal tumors, adrenal pheochromocytoma, extra-adrenal paragangliomas, and papillary endolymphatic sac tumors of the inner ear [4]. The association of hemangioblastomas with VHL disease makes the diagnosis and treatment of hemangioblastomas an even more clinically relevant topic of research exploration. The current review will discuss recent developments related to discovery of new factors and molecular pathways of potential clinical importance that are responsible of hemangioblastoma pathogenesis.

Keywords

VHL VEGF HIF P13K/AKTEpidemiology

Hemangioblastomas have an overall incidence of 0.141 per 100,000 person-years in the United States [5]. Some cases occur sporadically, while others are hereditary. Sporadic hemangioblastomas mostly appear in adults aged 30 to 65 years, with a higher prevalence in males [1, 2]. Hereditary cases are strongly linked to VHL and tend to develop at a younger age, with a mean age of 29 years. About 10% to 40% of primary symptomatic hemangioblastomas are related to VHL disease [2]. Epidemiologic data indicates important differences between sporadic and hereditary hemangioblastomas. Sporadic hemangioblastomas are usually solitary, while multiple tumors within the neuroaxis raise suspicion of the presence of VHL disease [4]. According to available data, the mean age of onset for sporadic cases is around 47 years, whereas VHL-associated hemangioblastomas had a mean age of onset of 29 years as of 1989 [2]. However, from 2010 to the present day, the mean age of onset for VHL-associated hemangioblastomas has tripled compared to sporadic cases, which have decreased seven-fold. Despite these differences, the male-to-female ratio of hemangioblastomas is 1-1.25:1 in both sporadic and hereditary cases [5]. In patients with sporadic hemangioblastomas, single lesions in the cerebellum are most common at presentation. Conversely, individuals with VHL disease may present with multiple lesions affecting the spinal cord, cerebellum, and brainstem. Although hemangioblastomas can develop throughout the central nervous system (CNS), the majority occur in the posterior fossa, especially within the cerebellum. About 45%–50% of hemangioblastomas are located in the cerebellum, 30%–40% in the spinal cord, and 5%–10% in the brainstem [4].

Clinical Presentation

Clinical manifestations vary depending on lesion size and location. CNS hemangioblastomas are typically located in the posterior fossa and spinal cord [4]. The disruption caused by CNS hemangioblastomas often develop gradually with slow-growing tumors that eventually exert enough mass effect on CNS structures to impair the function of adjacent areas [1]. This impairment can manifest as obstruction of cerebrospinal fluid flow through the fourth ventricle or the cerebral aqueduct [1]. Obstruction is often caused by posterior fossa hemangioblastomas, which can be associated with cyst formation. This obstruction leads to various symptoms, usually caused by larger tumors in the posterior fossa, which are often associated with cyst formation [6]. Pressure from cerebellar tumor formation can be associated with headache, gait imbalance, ataxia, and abnormal head position [6].

Large posterior fossa tumors can present with persistent headaches, obstructive hydrocephalus, cerebellar dysfunction such as ataxia, dysmetria, and diplopia, papilledema, cranial nerve deficits, altered mental status, nausea, and vomiting [5, 6, 7]. Notably, in rare and severe cases, large hemangioblastomas may bleed, leading to acute neurological deterioration potentially requiring emergent neurosurgical interventions. To date, only 19 cases of hemorrhagic hemangioblastoma have been reported [8]. Ocular hemangioblastomas involving the retina can cause retinal detachment, vision loss, retinal exudation, and vitreous and subretinal hemorrhage [8]. Spinal cord hemangioblastomas can lead to pain, dysesthesia, compression of the dorsal columns, hypoesthesia, motor deficits, urinary incontinence, and neuropathy [9, 10]. Neuropathic pain is often associated with a gain or loss of somatosensory function [9]. In syndromic settings such as VHL disease, hemangioblastomas can be accompanied by other neoplasms, including pheochromocytomas, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, renal cell carcinomas, and endolymphatic sac tumors [11, 12]. These may cause systemic symptoms like hypertension, hyperglycemia, hematuria, hearing loss, and abdominal discomfort, which further complicate the clinical picture and require multidisciplinary surveillance [13, 14, 15]. Moreover, benign vascular hamartomas can be found in patients exhibiting VHL. Although they may appear asymptomatic, hamartoma-related effects may present as impairments of hypothalamic functions (e.g., seizures, altered mental status, etc.), pulmonary symptoms (e.g., hemoptysis and coarse crackles on inspiration), coronary dysregulations (e.g., angina, palpitations, cyanosis, arrhythmia, and murmur), as well as induce PTEN/Cowden Syndrome. These syndromes involve multiple tissues, including breast, thyroid, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and mucocutaneous ailments [15]. Due to genetic linkage, patients presenting with VHL-related tumors, benign vascular hamartomas, clear cell renal cell carcinomas, pheochromocytomas, or pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms, are advised to undergo family history and possibly genetic testing.

Radiographic Features

Radiographic assessment plays a vital role in diagnosing, monitoring, and managing hemangioblastomas, especially in VHL patients, where multifocality and recurrence are frequent. A comprehensive understanding of radiologic features is crucial for differentiating hemangioblastomas from other CNS lesions and guiding surgical planning. MRI is the preferred modality for evaluating hemangioblastomas because of its superior soft tissue contrast and ability to distinguish both cystic and solid components. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI shows intense enhancement of the mural nodule, indicating the tumor’s rich vascularity [1, 16]. MRI scans with T1-weighted images reveal mural nodules that are hypo- or isointense, while T2-weighted images display hyperintense nodules, fluid-filled cystic components, and flow voids. On imaging, tubular and winding flow voids can be seen, representing major arteries and veins that supply and drain the tumor. These imaging features match well with histopathological findings, where the solid part of the tumor contains stromal cells scattered within a dense capillary network, and the cystic area results from fluid buildup caused by increased vessel permeability [16]. Solid, mural nodules in hemangioblastomas appear isodense on contrast computed tomography (CT) of the brain surrounded by cystic fluid, they are occasionally hyperdense on pre-contrast CT studies and show prominent homogeneous enhancement. The mural nodule can also demonstrate homogeneous enhancement post contrast administration. Additional findings, including hydrocephalus and edema, are visible on CT scans. These secondary features provide important clues about the tumor’s impact on surrounding brain structures and contribute to a thorough evaluation of the patient’s condition [13]. Detecting such complications early can help guide treatment decisions and predict potential neurological outcomes. Spinal cord hemangioblastomas, which make up about 1.6 to 2.1% of all spinal tumors, are particularly common in VHL patients. Studies found that nearly half of the cases of spinal hemangioblastomas are associated with a syrinx [17]. A multicenter study by Alsereihi et al. (2025) showed that gross total resection (GTR) was achievable in the majority of spinal hemangioblastoma cases, with favorable neurological outcomes, underscoring the importance of accurate preoperative imaging [11]. In the context of VHL disease, radiographic surveillance is paramount. Whole-neuroaxis MRI is advised to identify asymptomatic lesions and monitor recurrence [1, 10]. Multiplicity of enhancing nodules, especially in the cerebellum or spinal cord, strongly suggests VHL-associated hemangioblastomas [18]. Because of the complexities of VHL disease, a better understanding of the pathological and clinical features of hemangioblastomas in this population is essential for proper management.

Pathology

Hemangioblastomas are classified as WHO grade I category CNS tumors due to their usually benign presentations, and their high recovery rates after resection. Hemangioblastomas typically have solid and cystic components [3]. These components have different compositions, with the solid portion being comprised of the vasculature, and the cystic component being similar in composition to blood plasma. Due to the differences between the solid and cystic components of hemangioblastomas, it has been suggested that, in most cases, only the solid component containing the vasculature needs to be resected. Exceptions include cysts within the solid nodule or cysts that show peripheral enhancement on imaging; it is suggested that these cysts should be surgically removed [19]. Although histologically benign and slowly growing, hemangioblastomas tend to cause life-threatening complications due to the expansion of peritumoral cysts [20]. The morbidity and mortality associated with them can be reduced significantly if these lesions are appropriately diagnosed and treated. VHL syndrome-affected organs show microscopic developmental changes and the formation of preneoplastic lesions. Precursor cells are developmentally arrested at hemangioblasts that have biallelic VHL inactivation. However, these cells start to induce reactive angiogenesis through unknown triggers, and some may grow more quickly, advancing to hemangioblastoma. During growth, hemangioblastoma cells mimic the morphology of embryonic hemangioblasts, the precursors of hematopoietic and endothelial cells [19].

Microscopic Appearance

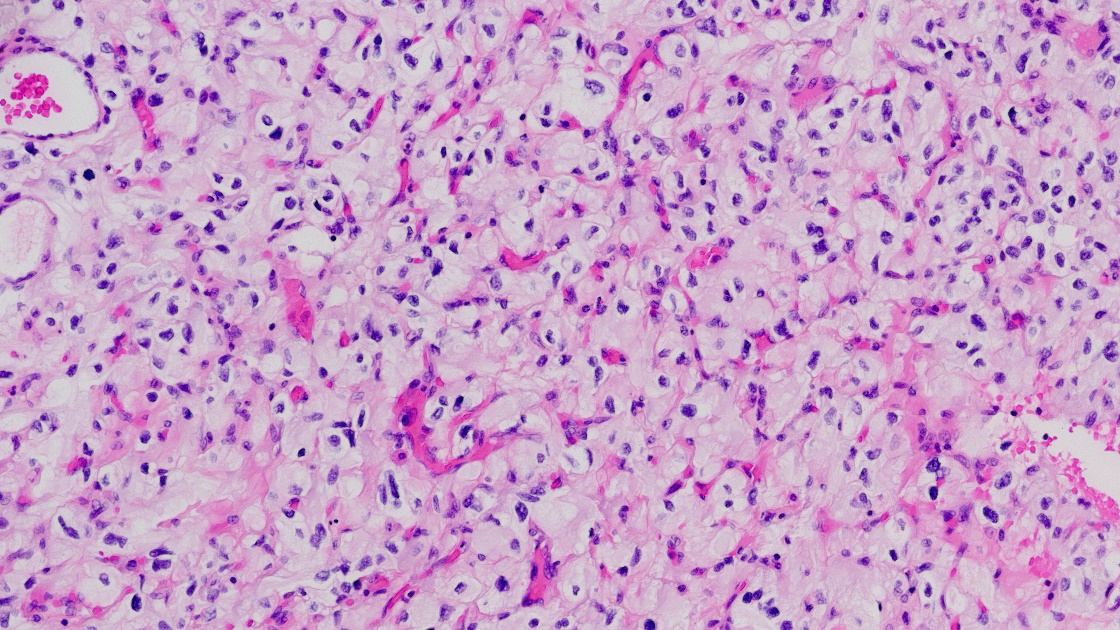

Histologically, hemangioblastomas consist of a collection of neoplastic stromal lipid-laden foamy cells, endothelial cells, and abundant capillaries. The stromal cells are typically lipid-laden and foamy, with clear cytoplasm containing vacuolated lipid droplets [3]. These cells are polygonal to spindle-shaped and often exhibit mild nuclear pleomorphism with degenerative atypia, although mitotic figures are rare [21]. The vascular component consists of thin-walled capillaries interspersed throughout the tumor, forming a reticulated network that is often surrounded by stromal cells and connective tissue [22], (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Figure 1

Hemagioblastona microscopic appearance: neoplastic stromal lipid-laden foamy cells, endothelial cells, and abundant capillaries.

The relative proportions of stromal to vascular elements can vary greatly among tumors, but the overall histologic pattern remains consistent. In classic CNS hemangioblastomas, the stromal cells are arranged between the capillary channels and the tumor borders [3]. The cytoplasm of stromal cells is often eosinophilic, and immunohistochemical staining reveals positivity for markers such as alpha-inhibin, S100, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and vimentin, supporting their mesenchymal origin [23]. In extra-neuraxial hemangioblastomas, such as those occurring in the kidney or soft tissues, the microscopic features are similar but may show site-specific immunophenotypic variations. For example, renal hemangioblastomas often express PAX8, which can complicate differentiation from clear cell renal cell carcinoma [3, 23]. Despite their benign histology, hemangioblastomas can occasionally exhibit significant nuclear atypia, mimicking malignancy, especially in unusual locations [24]. However, the absence of high mitotic activity, necrosis, and infiltrative growth helps distinguish them from more aggressive neoplasms [3]. The rich vascularity of hemangioblastomas contributes to their radiologic appearance and clinical behavior. The thin-walled vessels are prone to leakage, leading to cyst formation and peritumoral edema. This vascular architecture also underlies the intense enhancement seen on contrast imaging and the potential for hemorrhagic complications in larger lesions [25].

Location

While hemangioblastomas most frequently occur in the cerebellum, spinal cord, and retina, they have also been identified in less common regions of the CNS, including the brainstem—particularly the medulla oblongata and pons where their proximity to vital autonomic centers can lead to serious clinical complications [25, 26]. In rare cases, these tumors arise in supratentorial regions such as the cerebral hemispheres, thalamus, hypothalamus, pituitary stalk, or even the third and lateral ventricles, where they may resemble other cystic or vascular neoplasms, complicating radiologic and surgical planning [27, 28, 29]. In the spinal cord, while the cervical and thoracic segments are most affected, involvement can extend to the conus medullaris, filum terminale, and cauda equina [30, 31, 32]. The anatomical distribution and behavior of hemangioblastomas can vary considerably between sporadic and VHL-associated forms. Sporadic hemangioblastomas usually present as isolated, solitary lesions, most commonly in the cerebellum, and are diagnosed later in life with no family history or systemic findings [1]. In contrast, VHL-associated hemangioblastomas tend to be multifocal, recurrent, and appear earlier in life, often involving multiple CNS regions simultaneously, including rare sites such as the ventricular system and optic nerve pathways [1]. Additionally, hemangioblastomas in VHL are frequently accompanied by extracranial manifestations such as renal cell carcinoma, pheochromocytomas, and pancreatic cysts or neuroendocrine tumors, highlighting the importance of genetic evaluation in these cases [33]. Outside the CNS, isolated reports have documented hemangioblastoma-like lesions in soft tissues, peripheral nerves, and bones, although these are very rare and mostly linked to VHL mutations [33, 34]. Such unusual cases show the tumor’s broad histogenetic diversity and underscore the need for clinician awareness when encountering vascular lesions outside typical regions.

Association

Beyond typical VHL gene mutations, hemangioblastoma development involves a range of molecular, developmental, and environmental factors. Embryological abnormalities are increasingly seen as a key contributor. Hemangioblastomas may originate from residual hemangioblastic stem cells, multipotent precursors involved in early blood vessel formation, that abnormally remain in adult tissues due to incomplete developmental regression. These normally dormant cells can be reactivated by hormonal fluctuations or environmental triggers, leading to tumor formation [35]. This origin explains the tumor’s resemblance to embryonic vascular structures. Additionally, radiation exposure, though uncommon, presents a significant risk. Ionizing radiation—whether from therapy or excessive diagnostic imaging—can cause DNA damage and genomic instability, potentially triggering secondary vascular tumors such as hemangioblastomas [36]. This risk is especially relevant in patients with previous CNS interventions. The tumor microenvironment also plays a critical role in hemangioblastoma biology. An environment conducive to angiogenesis, marked by increased concentrations of VEGF, PDGF, and TGF-α, combined with immune cell infiltration, particularly tumor-associated macrophages creates a supportive niche for stromal cell proliferation and vascular remodeling [35, 37, 38]. Stromal cells, the tumor’s neoplastic component, thrive in this cytokine-rich environment, boosting tumor progression [38]. Genetic mosaicism and spontaneous mutations also play a role in sporadic hemangioblastomas. Post-zygotic mosaic mutations in the VHL gene can lead to isolated tumors without a family history, making diagnosis more complicated. Advanced molecular testing is needed to identify such low-level mosaicism. In sporadic cases, lesions are typically solitary; however, comprehensive imaging of the entire neuroaxis is recommended to exclude undetected multifocal disease, especially in patients with subtle or worsening neurological symptoms [1]. Systemic symptoms are more common in VHL-related disease due to other tumors, such as hypertension from pheochromocytomas, high blood sugar from pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, flank pain from kidney cancer, hearing loss from inner ear tumors, and cystadenomas affecting reproductive organs, which can be identified through imaging [4, 39, 40, 41, 42]. Factors such as developmental persistence, radiation damage, tumor-supporting environments, genetic mosaicism, and multi-organ involvement underscore the complexity of hemangioblastoma development. They highlight the importance of thorough diagnosis, complete imaging, and personalized monitoring, especially for unusual or isolated cases.

Treatment and Prognosis

Treatment of hemangioblastomas mainly involves surgical removal of the nodular part of the symptomatic tumor. Surgical resection at experienced centers can be curative with less morbidity. Hemangioblastomas have a high recurrence rate of 25% in the general population [1]. Microsurgical approaches have also been linked to stereotactic radiotherapy. Additionally, intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring (IONM) has shown a significant impact on post-operative outcomes [33]. Authors observed a strong correlation between pathological IONM findings and adverse results, while patients with nonpathological IONM findings were much less likely to develop new sensorimotor deficits after surgery [33]. Surgical removal is the preferred treatment for CNS hemangioblastomas, especially when tumors are symptomatic or exerting mass effect [1]. The decision regarding surgical management of symptomatic tumors depends on factors like symptoms, location, multiplicity, and tumor progression. The main goal of surgery is complete tumor removal while protecting the surrounding neural tissue. Due to the high vascularity of these tumors, careful preoperative planning is essential to minimize intraoperative bleeding. Preoperative embolization may be used to decrease the blood supply of tumor and enable safer resection and since most hemangioblastomas occur in the posterior fossa, a suboccipital craniotomy is usually performed to provide optimal access to the lesion. In this setting, microsurgical techniques, supported by a surgical microscope, are employed to remove the tumor. However, in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease who have multiple CNS hemangioblastomas, only lesions causing neurological symptoms are generally targeted for surgical resection [1].

Differential Diagnosis

Differentiating hemangioblastomas from other tumors is challenging because they share similar histological features with several neoplasms, especially those with abundant blood vessels and clear cells. Accurate diagnosis is essential, especially for tumors in unusual locations or in patients without von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) disease. A major challenge is distinguishing hemangioblastomas apart from metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), especially when tumors occur in the cerebellum or spinal cord [44]. Both can have clear cells, dense blood vessels, and react to markers like alpha-inhibin and S100 [24]. However, ccRCC usually expresses CD10 and carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX), which hemangioblastomas do not. In renal hemangioblastomas, the presence of PAX8 can complicate diagnosis, requiring molecular testing to confirm the tumor type [24, 44]. Hemangiopericytomas (now classified as solitary fibrous tumors) also exhibit vascular features similar to hemangioblastomas. They display a vascular pattern and test positive for STAT6 and CD34, while hemangioblastomas lack STAT6 and strong express alpha-inhibin [3, 24]. Vascular meningiomas, particularly those in the supratentorial brain region, can resemble hemangioblastomas on scans and under the microscope due to their blood vessels and clear cells. Immunohistochemistry helps distinguish them: meningiomas test positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) but negative for alpha-inhibin, which is opposite to hemangioblastomas [3]. In addition, other tumors to consider include paragangliomas, which may occur in the spinal cord and have a nested (“zellballen”) structure. Paragangliomas are positive for chromogranin and synaptophysin but negative for alpha-inhibin, helping to distinguish them from hemangioblastomas. Pilocytic astrocytomas may look similar on imaging because of cystic areas and mural nodules but display unique features like Rosenthal fibers and eosinophilic granular bodies that hemangioblastomas lack [3]. Overall, diagnosing hemangioblastoma requires integrating clinical information, imaging, microscopic examination, immunohistochemical staining, and molecular testing when needed. This comprehensive approach is essential, especially in sporadic cases or tumors in uncommon sites, to avoid misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment.

Molecular Pathways

A key factor in the growth and development of hemangioblastomas involves molecular pathways that result in excessive angiogenesis. Many different molecules with various chemical and biological properties have been identified as playing a role in developing hemangioblastomas. Some of these molecules and their related pathways include, but are not limited to, the actions of the VEGF/VEGFR family members and HIF (Hypoxia Inducible Factor) Oxygen dependent and independent pathways. Notably, many of these molecules are interconnected and may work in tandem to drive angiogenesis and tumor growth.

VEGF/VEGFR Family of Molecules

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been studied for nearly four decades. Research in the 1990s showed that high levels of VEGF contribute to their ability to develop a strong blood supply necessary for rapid growth and metastasis [44]. VEGF may serve as an important therapeutic tool for treating various pathological conditions characterized by excessive or defective growth of blood and lymphatic vessels. The VEGF receptors transduce signals that mediate endothelial cell proliferation, migration, organization into functional vessels, and the remodeling of vessel networks [45]. Different members of the VEGF family have been noted to significantly promote angiogenesis, initiate tumor growth, and facilitate metastatic spread [44]. The VEGF/VEGFR pathways use a combination of ligands and receptor interactions to exert their effects on vasculature and tumor growth. Agents that target these pathways can temporarily “normalize” tumor vessels and improve blood flow or oxygenation, which is associated with better treatment outcomes [46]. Different types of VEGF refer to the ligands, while the various forms of VEGFR refer to the corresponding receptors that these ligands bind to. The VEGF family of ligands includes VEGF-B, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D, along with placenta growth factor (PIGF) [46]. In addition to VEGF-A, there are VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, and placental growth factor (PIGF) ligands that belong to the same family [44]. VEGF-A influences and modulates endothelial cell sprouting, mitogenesis, cell migration, vasodilation, and vascular permeability [44]. VEGF-A is upregulated in tumors by both hypoxia and independent mechanisms [46]. Additionally, VEGF-A acts as an immunosuppressive cytokine in the tumor microenvironment, impairing the function of multiple immune cell types. VEGF-A affects macrophage function, which typically exhibits immunosuppressive activity, and is the primary cytokine secreted by tumor-associated M2 macrophages. VEGF-B activates embryonic angiogenesis and can influence metastasis independently of VEGF-A; VEGF-C and VEGF-D are known to heavily influence lymphangiogenesis in various tumors. PIGF ligands, most notably PIGF-1 and PIGF-2, are responsible for vasculogenesis, inflammation, and healing of cancer cells [46]. PIGF and VEGF-B have exclusive binding capacities to VEGF-1, initiating monocyte activation and differentiation [47]. VEGF-C and VEGF-D are glycoprotein mitogens for both vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells [47]. A common feature of the VEGF family of growth factors, including VEGF-B, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D, is the conservation of the central core region called the VEGF homology domain. A major part of this core region lies between the eight invariant cysteine residues; these are involved in inter- and intramolecular disulfide bonds in several of these dimeric growth factors [45].

General Mechanisms of Action Pertaining to Tumor Growth, and Other Associated Molecules Working in Tandem with VEGF

The upregulation of VEGF under physiological conditions enables adaptation to hypoxic stress, transient inflammatory processes, and tissue regeneration [48]. It also promotes increased neovascularization in solid and hematological tumors. VEGF ligands are produced through gene transcription, a process mediated by the Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1) complex. In response to hypoxic stress, HIF is stabilized and enhances VEGF-A transcription [46]. This process is influenced by the VHL protein, which is encoded by the VHL gene. The hypoxia-dependent accumulation of HIF-1α protein is mediated by a mechanism through which, in low oxygen conditions, HIF-1α becomes de-hydroxylated, preventing its degradation by the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein. Additionally, abnormal activation of receptor tyrosine kinases in tumor cells can also cause a hypoxia-independent increase in HIF-1α and VEGF-A [46]. Other molecules transcribed alongside VEGF include transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-alpha), erythropoietin, and placental growth factor-beta (PGF-Beta). The transcription of these molecules suggests that, similar to VEGF, TGF-alpha, platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor (PD-ECGF), and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) may be involved in angiogenesis and the progression and metastasis of tumor growth [49].

HIF Pathway

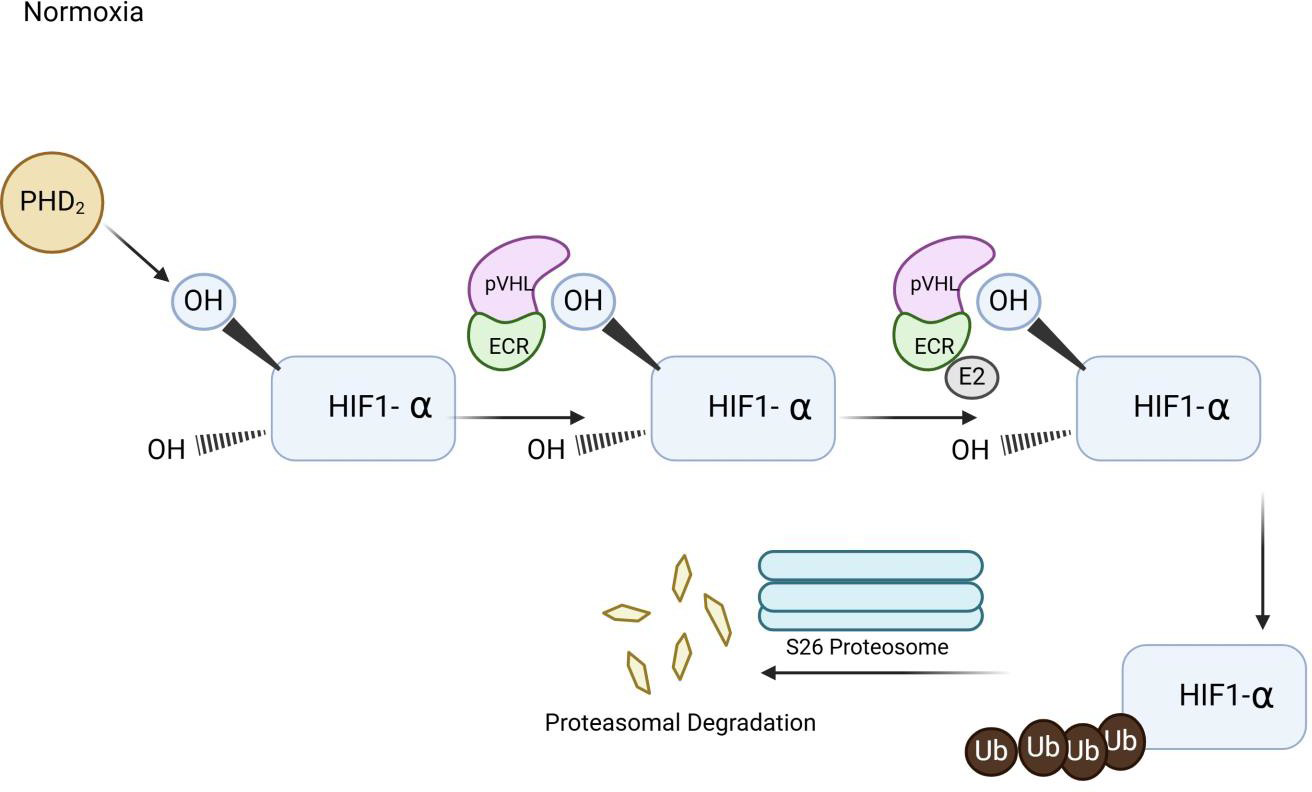

HIF-1 acts as a master regulator of cellular and systemic homeostatic responses to hypoxia by activating gene transcription [50]. The HIF-1 complex is a transcription factor composed of alpha and beta subunits. Each subunit has an N-terminal basic helix-loop DNA-binding domain. Two transactive domains drive the transcription process of the HIF gene into mRNA. An additional dimerization domain is found within the HIF-beta subunit. Proline residues, P402 and P56, along with an arginine residue, N803, regulate transcriptional activity and are essential for protein stability. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 2 Alpha (HIF-2 alpha) contains domains similar to those of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 Alpha (HIF-1 alpha) [51]. Typically, HIF-1 transcriptional activity depends on the amount of HIF-1 alpha, which is regulated by oxygen tension [50]. Under normoxic conditions, prolyl-hydroxylase domain protein 2 (PHD2) hydroxylates the HIF-α subunit using oxygen as a substrate, facilitating its recognition and binding by the VHL protein [48]. PHD2 signals for polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, which are crucial for maintaining HIF levels and homeostasis. PHD2 also employs hydroxylase-independent mechanisms that modify HIF activity [48]. When one or both proline residues are hydroxylated, a VHL protein-HIF-alpha complex forms and is targeted for degradation by the proteasome. Additionally, the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Complex (ECR) and E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme form a complex with the HIF-alpha subunit; the polyubiquitinated HIF-alpha is then degraded by the proteasome [48]. This process results in the polyubiquitination of HIF-α, marking it for degradation [48]. The coordinated actions of hydroxylation, VHL recognition, and ubiquitination keep HIF-α levels low under normal oxygen conditions (Figure 2). Furthermore, HIF-alpha proteins have arginine residues in their C-terminal transactional domain [50]. These residues are hydroxylated by dioxygenase factor, inhibiting HIF1-alpha. The hydroxylation inhibits the binding of p300 and CBP transcriptional coactivators [50]. When the HIF-1 alpha subunit is degraded, it cannot pass through cellular membranes or bind to the HIF-beta subunit to activate transcription of factors such as VEGF. Thus, during adequate oxygen levels, the VHL protein prevents HIF-1 alpha from entering the cell and inducing excessive angiogenesis by reducing the production of VEGF, erythropoietin, TGF-alpha, and PGF-beta (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Figure 2

Illustration of Hypoxia Induced Factor (HIF) Pathway. The diagram illustrates that when oxygen demand exceeds the supply, oxygen sensing pathway of Hypoxia Induced Factor is signaled to promote up-regulation genes involved in angiogenesis, erythropoiesis, and glycolysis.

HIF Oxygen Dependent Pathway

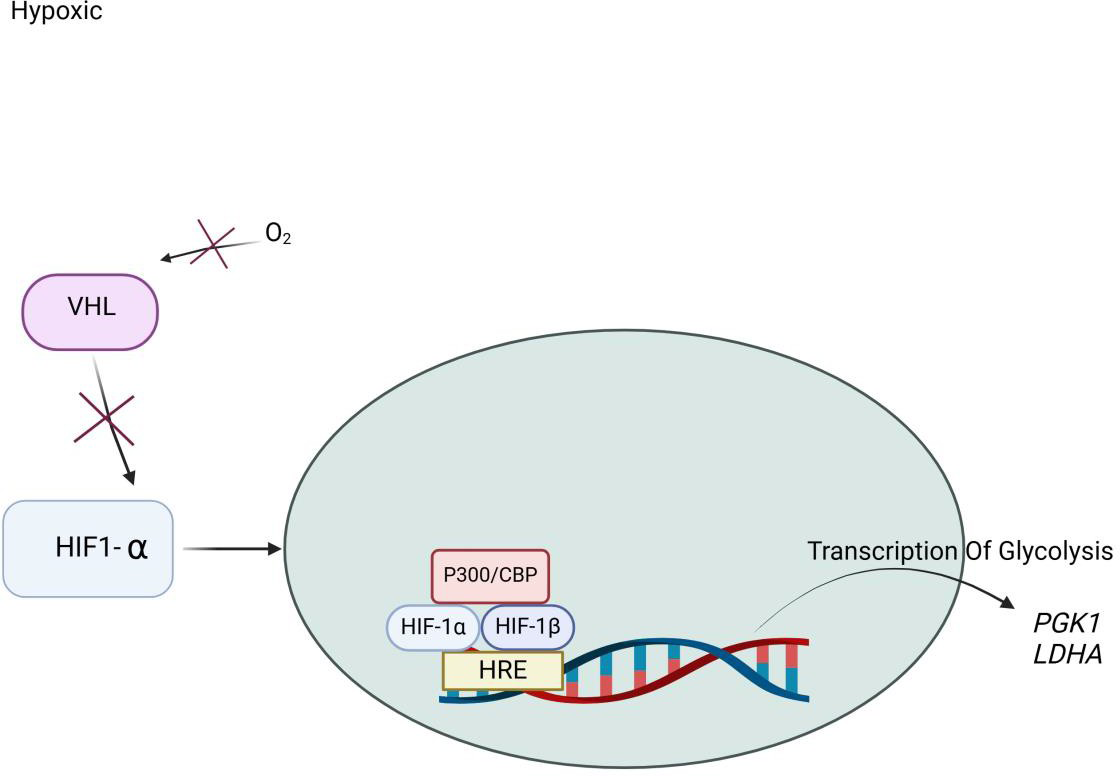

HIF-alpha1 has proven to be critical in promoting apoptosis under chronic hypoxia [52]. The gene encoding the pro-death factor Nip3 is induced by the hypoxic response and involves DNA sequence binding to hormone-receptor complexes (HRE), located in the promoter. Nip3 is found to be overexpressed in perinecrotic regions of human tumors. Under hypoxic conditions, the lack of oxygen prevents hydroxylation by PHD dioxygenases of the VHL protein [3]. HIF-alpha subunit associates with the HIF-beta subunit and binds to DNA [53]. P300 and CBP coactivators bind to the HIF-alpha subunit, forming a complex. This complex activates the transcription of target genes such as the LDHA gene. The LDHA gene encodes an isoenzyme of Lactate Dehydrogenase A, and the PDK1 gene. Under aerobic conditions, pyruvate is decarboxylated and oxidized by pyruvate dehydrogenase to generate acetyl-CoA. Pyruvate is oxidized to carbon dioxide, and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase phosphorylates and inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase [52]. HIF1-alpha stimulates the synthesis of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase. Under anaerobic conditions, lactate dehydrogenase converts pyruvate into lactate, with HIF1-alpha stimulating the synthesis of lactate dehydrogenase, thus promoting anaerobic glucose metabolism. As a result, there is no signal to degrade the HIF-alpha factor, so it remains undegraded and translocates to the nucleus (Figure 3).

The HIF-alpha factor can enter the cell, bind to DNA, and dimerize with the HIF-beta factor, leading to the transcription of factors such as VEGF, Prostaglandin-Derived Growth Factor Beta (PDGF-Beta), Erythropoietin, and Transforming Growth Factor-alpha (TGF-alpha) [54]. These factors all promote angiogenesis and increase red blood cell production. In the setting of hypoxia, this process helps facilitate the body’s ability to carry and distribute oxygen. The HIF-dependent hypoxic response pathway plays a prominent role in mediating the effects of many disease states such as cerebral and myocardial ischemia, pulmonary hypertension, and tumorigenesis.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Illustration of Hypoxia Induced Factor (HIF) Pathway under Hypoxic Conditions. Under hypoxic conditions, oxygen (O₂) availability is reduced, leading to the suppression of prolyl hydroxylation. As a result, Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) escapes recognition by the Von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor (VHL) complex and avoids proteasomal degradation. Stabilized Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) translocate into the nucleus, where it dimerizes with Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 Beta (HIF-1β also known as ARNT). Inside the nucleus, the Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-alpha/ Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 Beta (HIF-1α/HIF-1β) heterodimer forms a transactivation complex with co-activators such as p300/CBP. This complex binds to the Hypoxia Response Element (HRE) on target gene promoters, initiating transcription of genes that support cellular adaptation to low oxygen. Key glycolytic genes activated include: (Phosphoglycerate Kinase 1 (PGK1): catalyzes a key step in glycolysis and Lactate Dehydrogenase A (LDHA): converts pyruvate to lactate, regenerating NAD⁺ for continued glycolytic flux. This pathway enhances anaerobic energy production, promotes cell survival, and contributes to metabolic reprogramming under hypoxic stress.

HIF Oxygen Independent Pathway

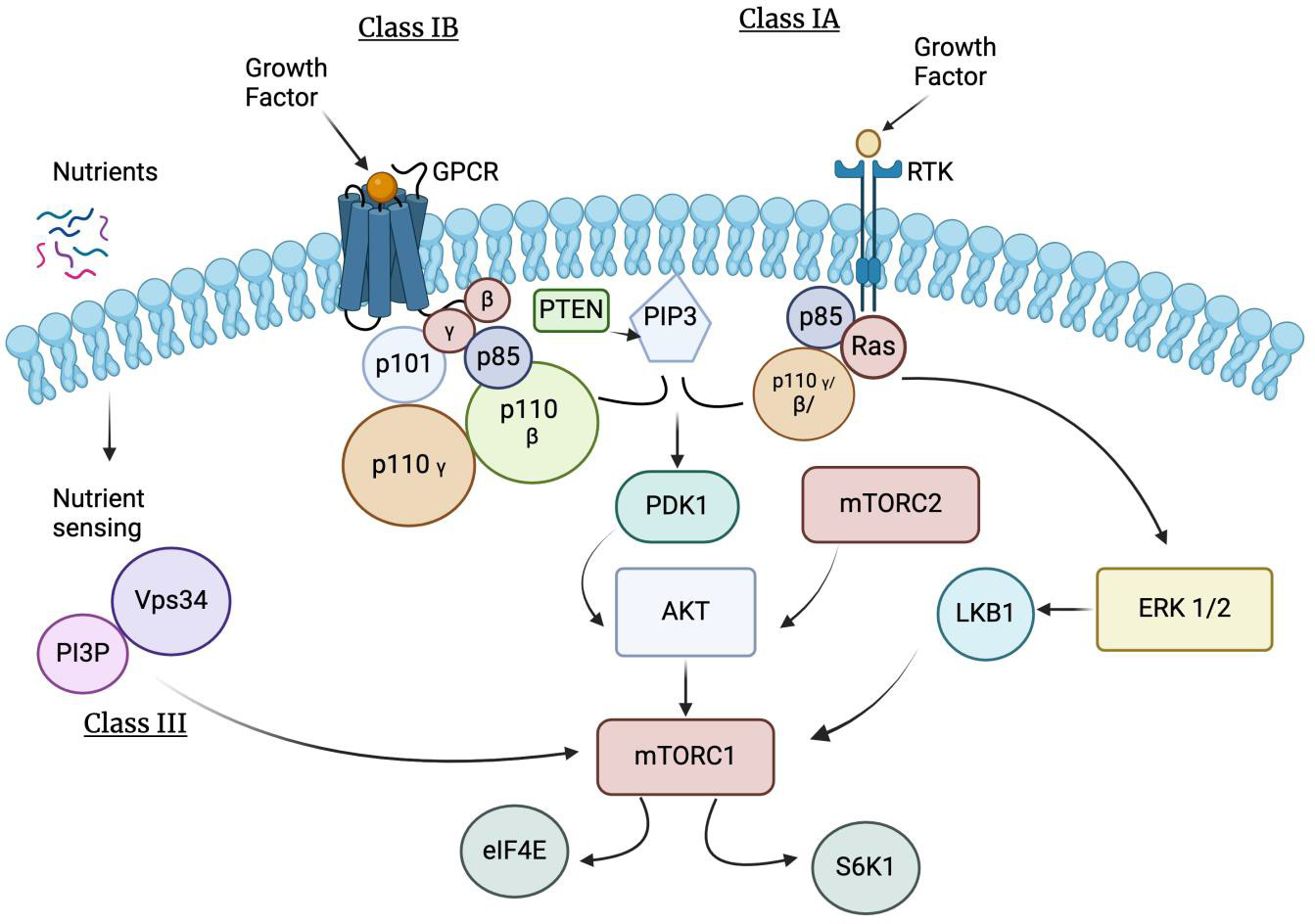

Oxygen levels primarily regulate HIF. However, there are situations where the HIF-1 complex can form even with adequate oxygen levels. This occurs due to decreased or nearly absent levels of the VHL protein [55]. When VHL proteins are missing or altered, HIF-2 alpha cannot be properly degraded. This results in a buildup of HIF, causing cells to divide abnormally and produce new blood vessels. Consequently, this leads to an increase in the production of tumors and cysts [51]. Additionally, certain pathways activate HIF signaling through specific proteins, including Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B (P13K/AKT) or protein kinase C (PKC), influencing HIF-alpha stability independently of oxygen levels. The P13K/AKT pathway is activated by growth factor receptors like Erythroblastic Leukemia Viral Oncogene Homolog B (ErbB), along with other genes, which activate AKT, localizing it to the plasma membrane. The P13K/AKT pathway is regulated by phosphorylation of downstream effectors that affect cell survival, proliferation, and cycle. PKC, an isoenzyme activated by phorbol esters, promotes tumor growth [56] (Figure 4). Certain signaling pathways can also increase HIF-alpha mRNA translation, resulting in higher HIF levels under normal conditions. Factors such as heat shock proteins (HSPs) and molecular chaperones help stabilize HIF-α, thereby modulating its degradation based on oxygen levels [57, 59]. Regardless of oxygen levels, if little or no VHL protein is available to bind with the HIF-alpha subunit, the HIF-alpha subunit will not be targeted for proteasomal degradation. Instead, it will enter the cell, where it will form the HIF-1 complex, and lead to VEGF production (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Figure 4

Illustration of Hypoxia Induced Factor (HIF) Oxygen Independent Pathway. This activation signals specific proteins including Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/ Protein Kinase B (PKB or P13K/Akt) or by protein kinase C (PKC). Growth factors activate specific receptor tyrosine kinases, triggering intracellular signaling cascades that converge on the Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/ Protein Kinase B or Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, leading to Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) stabilization and transcriptional activity. Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), protein kinase B (PKB/AKT), and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway are frequent events in cancer that facilitates tumor formation. Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase are a large family of lipid kinase enzymes divided into three classes termed Class I (subdivided into Class IA and IB), Class II, and Class III. Class IA PI3Ks are heterodimers containing a catalytic subunit (p110α, p110β, or p110δ, encoded by Posphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Alpha (PIK3CA), Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Beta (PIK3CB), and Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-Bisphosphate 3-Kinase Catalytic Subunit Delta (PIK3CD)) and a regulatory subunit (p85α/p55α/p50α, p85β or p55γ, encoded by Phosphoinositide-3-Kinase Regulatory Subunit 1 (Alpha) (PIK3R1), Phosphoinositide-3-Kinase Regulatory Subunit 2 (Beta) (PIK3R2), and Phosphoinositide-3-Kinase Regulatory Subunit 3 (Gamma) (PIK3R3)) that controls protein localization, receptor binding, and activation. Class IA isoforms are ubiquitously expressed, except for p110δ and p55γ that are primarily expressed in the hematopoietic/central nervous systems and testes. Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) can activate p110α, p110β, and p110δ catalytic isoform. Class IA Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase initiate a wave of downstream signaling events by synthesizing the lipid secondary messenger phosphatidylinositol 3, 4, 5 trisphosphates (PIP3) from phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate (PIP2) to mediate cell growth, proliferation, autophagy, and apoptosis [58]. The tumor suppressor, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN), negatively regulates PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling by converting PIP3 back to PIP2.

Certain signaling pathways can also increase HIF-alpha mRNA translation, resulting in higher HIF levels under normal conditions. Factors such as heat shock proteins (HSPs) and molecular chaperones help stabilize HIF-α, thereby modulating its degradation based on oxygen levels [57, 59]. Regardless of oxygen levels, if little or no VHL protein is available to bind with the HIF-alpha subunit, the HIF-alpha subunit will not be targeted for proteasomal degradation. Instead, it will enter the cell, where it will form the HIF-1 complex, and lead to VEGF production (Figure 4). The tumor suppressor, phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN), negatively regulates PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling by converting PIP3 back to PIP2 [58].

Normal VHL protein functions involve cell growth regulation. It modulates hypoxia signaling through hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), a complex responsible for stimulating growth factors. Loss of VHL function results in the loss of HIF. This increases the expression of growth factors even without hypoxia, promoting angiogenesis and tumor growth. The lack of adequate VHL protein can occur in various ways. In VHL syndrome, the absence of the VHL gene means there is a near or complete inability to transcribe and translate the VHL genetic code into VHL protein. In other cases, even when the VHL gene is present, processes such as methylation (adding methyl groups) near the site of the VHL gene can reduce its transcription and translation. In either scenario, the reduction or near absence of VHL protein leads to a lack of regulation of the HIF-alpha subunit [60].

Consequently, the HIF-alpha subunit enters cells and binds with the HIF-beta subunit, resulting in uncontrolled transcription and translation of VEGF, TGF-alpha, erythropoietin, and PGF-beta [60]. Because of this, uncontrolled angiogenesis and increased red blood cell levels occur, raising the likelihood of vasculature developing into tumors and/or cysts, forming hemangioblastomas [61, 62].

Clinical relevance

The HIF pathway offers an opportunity to explore ways to slow the growth of tumor blood vessels. Various drugs can target components of the HIF pathway. These newer drugs are more efficient than those specifically used to target VEGF. Some examples of these drugs, which are being tested in clinical trials, include Roxadustat, Vadadustat, and Daprodustat. Interestingly, other drugs, compounds, and extracts have been observed to indirectly inhibit the HIF pathways. This occurs through two mechanisms: inhibitors of HIF-1 alpha activity and inhibitors of HIF-1 alpha-related signaling. In turn, HIF-1 alpha activity inhibitors can be further divided into distinct categories. Examples include those that affect the degradation of HIF-1 alpha; interfere with the transcription and gene expression of HIF-1 alpha; and those that block the formation of the HIF-1 complex. Because of the variety of compounds and ways the HIF-1 pathway can be influenced, there is significant clinical potential for drug development in this area to suppress tumor growth and spread. Besides targeting the HIF pathway, several drugs directly target VEGF to inhibit angiogenesis. Many of these drugs, classified as angiogenesis inhibitors, include monoclonal antibodies designed to bind to VEGF receptors, preventing VEGF molecules from binding to their receptors and thus blocking their effects. Some examples of these drugs include Bevacizumab, Axitinib, and Everolimus [63].

Conclusion

Various factors can influence the growth, development, and spread of hemangioblastomas. The HIF-1 pathway, VEGF ligands and receptors, all contribute to the uncontrolled growth and spread of hemangioblastomas. These molecules interact, resulting in uncontrolled cancer growth. It can be argued that inhibiting HIF-1 under certain conditions may be beneficial for controlling excessive tumor growth. Despite this, VEGF-A remains a major target, and many antiangiogenic drugs have already been developed and extensively tested. Currently, the vascular pathways active in hemangioblastomas are not fully understood and more research is required before the ideal therapeutic drug target and therapy could be developed.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No sources of support were received for this study by any of the authors.

Original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Original image file for Figure 1

Original image file for Figure 2

Original image file for Figure 3

Original image file for Figure 4

References

-

Hemangioblastoma.

StatPearls [Internet]. 2025.Jan-

Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK606126/ - A 10-year retrospective study of hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system with reference to von Hippel–Lindau disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18(7):939-944. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2010.12.050

- Neuropathologic features of central nervous system hemangioblastoma. J Pathol Transl Med. 2022;56(3):115-125. doi:10.4132/jptm.2022.04.13

- von Hippel–Lindau disease: a clinical and scientific review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(6):617-623. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.175

- Incidence, prognostic factors and survival for hemangioblastoma of the central nervous system: Analysis based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Front Oncol. 2020;10:570103-. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.570103

- Hemangioblastoma and von Hippel–Lindau disease: genetic background, spectrum of disease, and neurosurgical treatment. Childs Nerv Syst. 2020;36(10):2537-2552. doi:10.1007/s00381-020-04712-5

- A Review of Posterior Fossa Lesions. Mo Med. 2022;119(6):553-558.

- Recurrent hemorrhage in hemangioblastoma involving the posterior fossa: Case report. Surg Neurol Int. 2017;8:122-. doi:10.4103/sni.sni_91_17

- Spinal hemangioblastomas and neuropathic pain. World Neurosurg. 2021;149:e109-e115. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2021.01.070

- Spinal cord hemangioblastomas in von Hippel–Lindau disease. Neuro-Oncology Advances. 2024;6(Suppl 3):iii66-iii72. doi:10.1093/noajnl/vdad153

- Neurological Outcome of Spinal Hemangioblastomas: An International Observational Multicenter Study About 35 Surgical Cases. Cancers. 2025;17(9):1428-. doi:10.3390/cancers17091428

- VHL-associated optic nerve hemangioblastoma treated with stereotactic radiosurgery. J Kidney Cancer VHL. 2018;5(2):1-6. doi:10.15586/jkcvhl.2018.104

- New biology of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Pract. 2022;28(12):1125-1133. doi:10.1016/j.eprac.2022.09.003

- Sporadic Renal Hemangioblastoma: A Case Report of a Rare Entity. Cureus. 2023;15(12):e47102-. doi:10.7759/cureus.47102

-

Hamartoma.

StatPearls. 2023.

Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562298/ - Contribution of MRI in the diagnosis of haemangioblastomas. Journal of Neurology. 1987;234(6):388-392. doi:10.1007/BF00314364

- Sporadic hemangioblastoma of cauda equina: a case report and brief literature review. J Craniovert Jun Spine. 2022;13(3):265-270. doi:10.4103/jcvjs.jcvjs_87_22

- Dual manifestations: spinal and cerebellar hemangioblastomas indicative of von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Radiol Case Rep. 2024;1(9):5000-5006. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2024.07.15

- Haemangioblastoma (central nervous system). Reference article. Radiopaedia.org. . doi:10.53347/rID-1412

- The clinical experience of recurrent central nervous system hemangioblastomas. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2014;21(6):1005-1010. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2013.12.025

- Atypical spindle cell/pleomorphic lipomatous tumor with sarcomatous transformation: Clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of 4 cases. Modern Pathology. 2024;37(4):100454-. doi:10.1016/j.modpath.2024.01.034

-

Pathology, genetics and cell biology of hemangioblastomas.

Histol Histopathol. 1996;11(4):1049-61.

Available from: https://digitum.um.es/digitum/bitstream/10201/18903/1/Pathology%20genetics%20and%20cell%20biology%20of%20hemangioblastomas.pdf -

Primary hemangioblastoma of the kidney with molecular analyses by next generation sequencing: a case report and review of the literature.

Diagn Pathol. 2022;17:34-.

Available from: https://diagnosticpathology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13000-022-01213-8 -

Clinicopathologic features of hemangioblastomas with emphasis on unusual locations.

Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2017;10(2):1792-800.

Available from: https://e-century.us/files/ijcep/10/2/ijcep0041392.pdf -

α-SMA positive vascular mural cells suppress cyst formation in hemangioblastoma.

Brain Tumor Pathol. 2023;40(3):176-184.

Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10014-023-00465-6 -

Intramedullary hemangioblastoma of the medulla oblongata — two case reports.

Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2008;48(8):489-493.

Available from: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/nmc1959/38/8/38_8_489/_article -

Hemangioblastoma of the pons and middle cerebellar peduncle.

Neurosurg Focus Video. 2019;1(2):V6-.

Available from: https://thejns.org/video/view/journals/neurosurg-focus-video/1/2/article-pV6.xml - Supratentorial hemangioblastoma at the anterior skull base: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10(26):9518-9523. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v10.i26.9518

-

Brainstem hemangioblastoma and sellar mass.

J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012;3(3):283-286.

Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3505365/ - Hemangioblastoma in the lateral ventricle: An extremely rare case report. Front Oncol. 2022;12:948903-. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.948903

-

Spinal hemangioblastoma located in the conus medullaris: Case report.

Turkish Neurosurgery. 2006;16(4):194-196.

Available from: https://turkishneurosurgery.org.tr/pdf/pdf_JTN_103.pdf - Hemangioblastoma of the cauda equina. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1985;87(1):55-59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0303-8467(85)90070-8

-

Sporadic hemangioblastoma of cauda equina: An atypical case report.

Surg Neurol Int. 2019;10:60-.

Available from: https://doi.org/10.25259/SNI-127-2019 - van Leeuwaarde RS Ahmad S van Nesselrooij B Zandee W Giles RH Von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2000 [updated 2025 May 1] 2000 [updated 2025 May 1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1463/

- Extraneuraxial hemangioblastoma: A clinicopathologic study of 10 cases with molecular analysis of the VHL gene. Pathol Res Pract. 2018;214(11):1748-1757. doi:10.1016/j.prp.2018.05.007

- Von Hippel-Lindau disease-associated hemangioblastomas are derived from embryologic multipotent cells. PLoS Med. 2007;4(2):e60-. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0040060

- Radiation-induced cavernous hemangiomas: case report and literature review. Can J Neurol Sci. 2009;36(3):303-310. doi:10.1017/S0317167100007022

- Pathological and clinical features and management of central nervous system hemangioblastomas in von Hippel–Lindau disease. Neurooncol Pract. 2014;1(3):103-114.

-

Stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment: accomplices of tumor progression?.

Cell Death Dis. 2023;14:587-.

Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-023-06110-6 - Pancreatic involvement in von Hippel–Lindau disease: molecular genetics, clinical features, and management. Am J Med. 1999;106(6):622-629.

- Diversities of mechanism in patients with VHL syndrome and diabetes: a report of two cases and literature review. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2023;16:3301-3309. doi:10.2147/DMSO.S386169

- Renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:125-137. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2308576

-

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma with hemangioblastoma-like features: A previously unreported pattern of ccRCC with possible clinical significance.

Histopathology. 2014;65(5):637-646.

Available from: https://www.clinicalkey.com/#!/content/playContent/1-s2.0-S0302283814004035 - Molecular mechanisms and future implications of VEGF/VEGFR in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29(1):30-39. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-1366

- Novel VEGF family members: VEGF-B, VEGF-C and VEGF-D. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001;33(4):421-426. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00027-9

- Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Its Receptor (VEGFR) Signaling in Angiogenesis. Genes Cancer. 2011;2(12):1097-1105. doi:10.1177/1947601911423031

- Molecular biology of the VEGF and the VEGF receptor family. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2000;26(5):561-569.

- Role and regulation of prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(5):635-641. doi:10.1038/cdd.2008.10

- TGF-alpha as well as VEGF, PD-ECGF and bFGF contribute to angiogenesis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2000;17(3):453-460. doi:10.3892/ijo.17.3.453

- Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF)-1 regulatory pathway and its potential for therapeutic intervention in malignancy and ischemia. Yale J Biol Med. 2007;80(2):51-60.

- Elsevier Von Hippel-Lindau Protein - an overview ScienceDirect.com; [cited 2025 Aug 15] https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/von-hippel-lindau-protein

- Expression of the gene encoding the proapoptotic Nip3 protein is induced by hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(16):9082-9087. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.16.9082

- Emerging Roles for Eph Receptors and Ephrin Ligands in Immunity. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1473-. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01473

- Action Sites and Clinical Application of HIF-1a Inhibitors. Molecules. 2022;27(11):3426-. doi:10.3390/molecules27113426

- HIF-1α pathway: role, regulation and intervention for cancer therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2015;5(5):378-389. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2015.05.007

- Targeting PI3K/Akt signal transduction for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):425-. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00828-5

- Author Correction: High systemic and tumor-associated IL-8 expression associates with a compromised clinical benefit to PD-L1 blockade in NSCLC. Nat Med. 2021;27(3):546-. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01246-4

- The PI3K-AKT-mTOR Pathway and Prostate Cancer: At the Crossroads of AR, MAPK, and WNT Signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4507-. doi:10.3390/ijms21124507

-

The primary pathway from PI3K to mTORC1: Switching on Rheb.

Trends Biochem Sci. 2015;40(11):687-689.

Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:163162060 - The VHL tumor suppressor: master regulator of HIF. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15(33):3895-3903. doi:10.2174/138161209789649394

- Moini J Samsam M Hemangioblastoma - an overview In: Moini J, Samsam M, editors. Epidemiology of Brain and Spinal Tumors. 2021. [Accessed 2025 Aug 15] 2021 https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/hemangioblastoma

- U.S. National Library of Medicine HIF1A hypoxia inducible factor 1 subunit alpha [Homo Sapiens (human)] - gene - NCBI National Center for Biotechnology Information. [Date Accessed] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/3091

-

Hypoxia signaling in human diseases and therapeutic targets.

Nat News. 2019 Jun 20.

Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s12276-019-0235-1